Economists like to work on the margins and the marginal change. Due to this, it may be argued that economics is a relative sport. In listening to the pundits on Fox Business and comments in the Wall Street Journal recently, there has been a shift from a “soft” landing to the likelihood of a recession. Part of that discussion is driven by changes in several measures – most notably changes in labor market conditions. But it matters greatly what is used as a baseline for estimating that change.

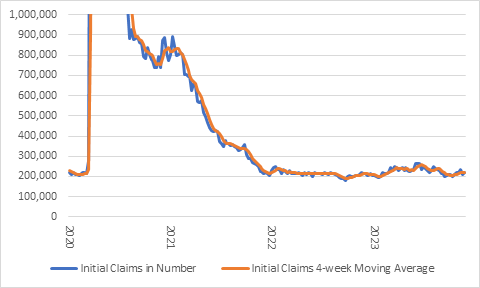

In looking at Initial Claims and Continued Claims unemployment data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and retrieved from FRED (fred.stlouisfed.org), the timing of change matters. For Initial Claims, the month-over-month (M/M) change is less than -1%, while the 4-week moving average is about 4.4%. So depending on the measure, the claims filed are about the same, or somewhat higher than a month ago. If the year-over-year (Y/Y) period is considered, Initial Claims filings are up about 5,000 or 2.4%, with the 4-week moving average up 7,500 or 3.5%. The Y/Y is probably setting off alarm bells that the economic sky is falling. But wait! When current data are compared to pre-COVID initial filings from the first week of 2020, claims are down just under 2% and the 4-week moving average is down almost 4%. So, is the sky falling back to trend? Possibly. Take a look at Figure 1.

Figure 1: Initial Claims

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

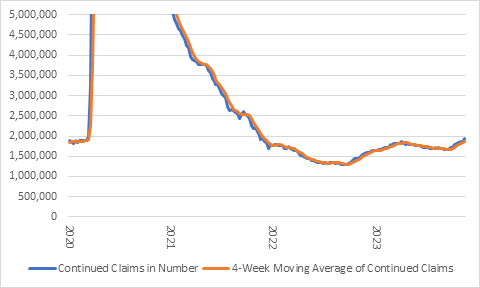

Continuing claims, or those workers who filed an initial claim and then experienced at least a week of unemployment, may tell a slightly different and more troubling story. The M/M trend for initial filings is up 6.3% and up 24% for Y/Y claims. Similarly the continued 4-week moving average for M/M is up about 6.1% and the Y/Y at 28.3%. This is troubling, at least in the short run. But when compared to the data from January of 2020, the Continued Claims are up 2.5% and the 4-week moving average is up 1.3%. Relatively speaking, Continued Claims, and as shown in Figure 2, are at about the same level now that they were in early 2020.

Figure 2: Continued Claims

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

It may be argued that the figures above don’t show enough history, and that using January of 2020 is biased. However, it is also arguable that choosing any data points for analysis and comparisons is biased. But in looking forward into 2020 early in that year, and for much of the first quarter, most economists predicted a robust economy with no recession in sight. While many saw COVID-19 affecting supply chains in the Pacific Rim, few saw the broader impacts that would send the global economy into a relatively short recession. Thus, it is arguable that it is a pretty good place to start.

There are, however, some signs that the economy is likely to slow. Current forecasts from the University of Michigan sees real GDP growth at 1.7%i. Similarly, the Survey of Professional Forecasters at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphiaii also expect 1.7% growth in real GDP for 2024. The forecast for future real GDP growth is well below the Q3 estimate from the Bureau of Economic Analysisiii (BEA) of 5.2% growth in Q3, which was revised upward in this second estimate. But as reported on December 6th, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNowiv estimate of Q4 GDP growth is 1.3%.

What are some factors that may support the slowing in the economy that aren’t necessarily indicated in the labor market data? Some could include:

- The ISM Nonmanufacturing Index for November is still in expansion at 52.7—if the Index slips below 50 it is in contraction.

- The number of job openings reported in the JOLTS report for October is down M/M 820,000 to 8.7 million.

- Vehicle sales are well below trend of 16.7 million units to the BEA’s reporting 15.3 million units in November.

- The ISM Manufacturing Index remains in contraction below 50 at 46.7 for November. This was the same level as October.

- Pending home sales are down 1.5% for October.

While the economy appears to be strong, at least from a labor market perspective, there are signs of weakness in other economic measures that support the outlook from many the forecasters that the U.S. economy will grow at lower rates than in 2023.